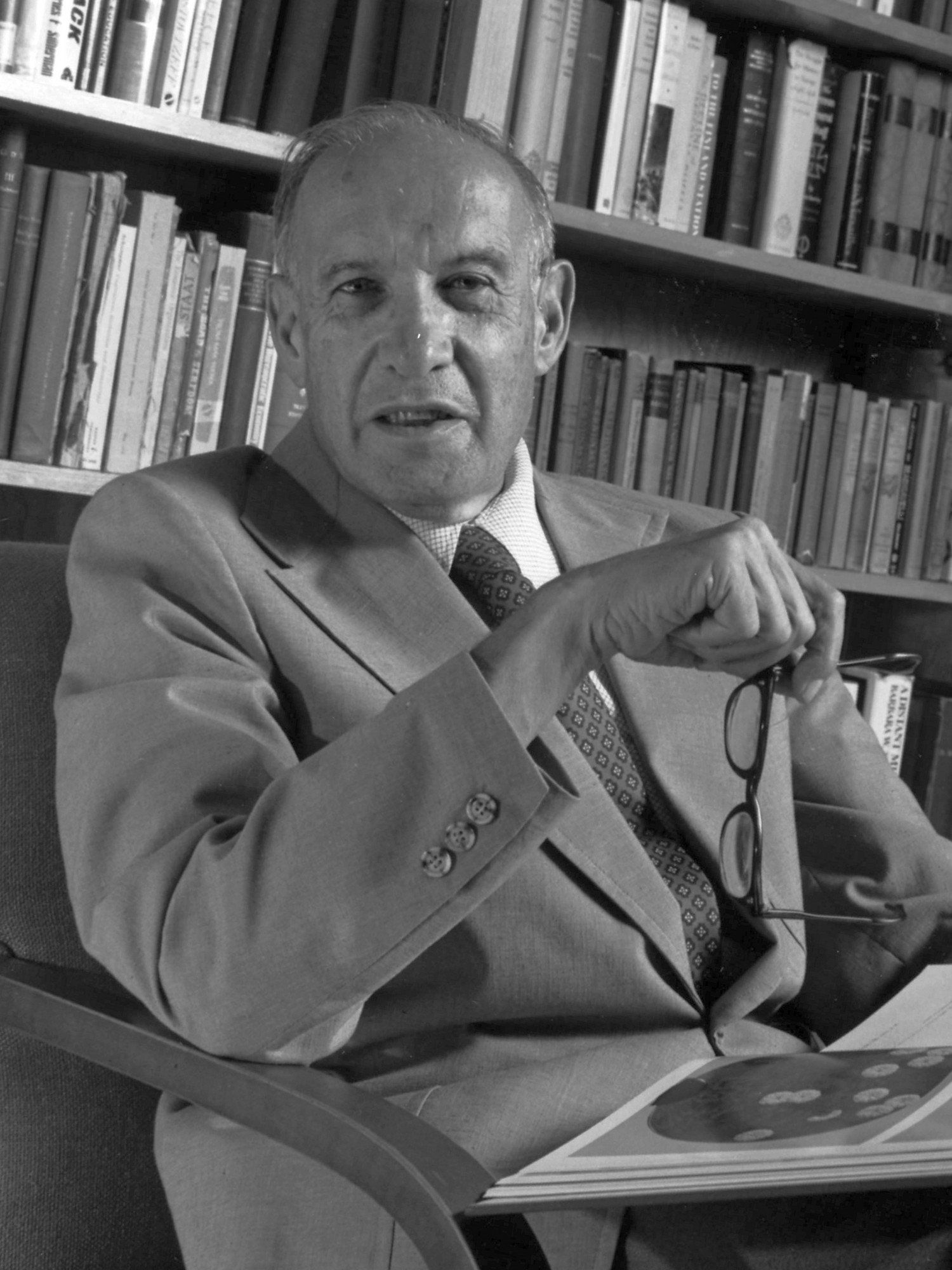

By Karen E. Linkletter, Ph.D.

•

April 18, 2022

The central theory of the fascist concept of Heroic Man is the self-justification of personal sacrifice – one of the oldest and most deeply-rooted ritual concepts of mankind, which has always been used to placate or to banish demonic forces…Only through the sublimation of a senseless immolation into a magical offering can the very elements of irrational warfare be rationalized again. The isolation of the individual in machine war, the anonymity of his sacrifice, and the blind arbitrary rule of fate appear as ends in themselves in the self-justification of individual sacrifice. It is a common and stupid mistake to look at this exaltation of sacrifice in totalitarianism as mere hypocrisy, self-deception, or a propaganda stunt. It grew out of deepest despair. Just as nihilism in the Russia of 1880 attracted the noblest and bravest of the young people, so in Germany and Italy it was the best, not the worst, representatives of the postwar generation who refused to compromise with a world that had no genuine values worth dying for and no valid creed worth living for. – Peter Drucker, The End of Economic Man , pp. 191-192. Recent events have caused me to revisit MLARI’s Vision Statement, which we revised a little less than a year ago. Our Vision is: A functioning society of institutions that ethically respects all of its constituencies and resists totalitarianism and autocracy in order to realize individual dignity. The events taking place in Ukraine give us all pause as we consider the fragility of democracy and the brazenness of authoritarian regimes bent on asserting raw power in any form. I have resisted writing about the events in Ukraine for a number of reasons, but I feel compelled to address them from the perspective of Peter Drucker’s experience with and remarks about totalitarianism. I am by no means an expert in international relations, Russia, the former Soviet Union, or any other political aspect of current events. However, I would like to present Drucker’s early observations of authoritarian societies and show how we can learn from them. Drucker’s theory of management is based on his concept of a Functioning Society of Institutions. Like many who witnessed the rise of totalitarianism in the 1930s, Drucker sought an explanation for why this form of governance was so appealing to people. What conditions made the rise of the Nazis possible, and how could such an event be prevented from ever happening again? Drucker published his book, The End of Economic Man in 1939. In this book, he developed his own explanation for totalitarianism and its appeal. Drucker’s main thesis in The End of Economic Man is that the traditional institutions of European society had broken down, and so had people’s belief in the systems that held society together. Out of this analysis, Drucker developed his concept of a Functioning Society of Institutions. How can the institutions of a society persist, so that there isn’t such a complete breakdown again? Where can people find status and function in society? What institutions or organizations can provide meaning to existence? What could help to prevent the alienation that drove the rise of totalitarianism in the 1920s and 1930s? When Drucker came to the United States, he looked around and saw, with the rapid growth of industrial capitalism, the increasing prominence of the corporation, particularly in the manufacturing sector. Consequently, his subsequent works on industrial capitalism ( The Future of Industrial Man and his analysis of General Motors, The Concept of the Corporation ) analyzed the nature of industrial organizations and how they could provide status and meaning for those employed there. As a result, Drucker’s early work on management focused on how to make corporate organizations functioning institutions that were not just economic entities but also social ones. But key to understanding Drucker’s analysis of totalitarianism is also his early critique of economic systems – both capitalism and Marxism. The title of Drucker’s book, The End of Economic Man , telegraphs his argument. The conception of humans (man) as beings ruled by economic decisions results in inherent contradictions with the belief in equality. Economic freedom, says Drucker, does not result in human equality; in fact, it results in quite the opposite: “Economic progress does not bring equality, not even the formal equality of ‘equal opportunity.’ It brings instead the new and extremely rigid unequal classes…” (p. 39). Marxism also fails to bring about its promise of equality. As a result, the two primary creeds of “Economic Man” (capitalism and Marxism) made no sense to early 20th century Europeans: “The class society of the capitalist reality is irreconcilable with the capitalist ideology, which therefore ceases to make sense. The Marxist class war, on the other hand, while it recognizes and explains the actual reality, ceases to have any meaning because it leads nowhere. Both creeds and orders failed because their concept of the automatic consequences of the exercise of economic freedom by the individual was false” (pp. 44-45). To fill the void of the end of Economic Man, totalitarianism proffers Heroic Man as a solution to hopelessness and despair. The model of self-sacrifice to a cause or great leader attracts those who believe society holds no “genuine values worth dying for and no valid creed worth living for.” Drucker asks us to take this aspect of totalitarianism very seriously, remarking that the celebration of self-sacrifice and subordination of the individual to society had a history in Europe, notably in the nihilism movement in late 19th-century Russia. Nihilism was a movement that began among well-educated elites in the mid-1800s. Rather than upholding traditional cultural values and the optimism of the early 19th century, these intellectuals instead embraced a rebellion against societal norms and advocated for revolutionary change and destruction of established institutions (class and family structures, church and state). As Drucker notes in The End of Economic Man , many of those attracted to nihilism were from the upper ranks and nobility of society. His point is that authoritarian ideals are not just supported by those at the bottom tier of society. This discussion illustrates the importance of one’s worldview, and the role it plays in the idea of Management as a Liberal Art. The notion of ‘worldview’ can seem quite esoteric and removed to many people, but Drucker’s analysis of totalitarianism sheds light on how important it is to not just one’s personal philosophy of life, but also to entire systems of governance. Drucker’s solution to the end of Economic Man (and the ultimate end of Heroic Man) was a “new, positive noneconomic concept of Free and Equal Man” (p. 268). But in Putin’s Russia, we can see elements of the Heroic Man worldview at work. When Putin was elected to a second term as President in 2004 with some 70 percent of the vote, the Russian economy benefitted from a sharp rise in oil prices, translating into a higher standard of living for Russians. After being prevented from running again in 2008 because of term limits at the time, Putin came back in as President in 2012. However, the Russian economy was much weaker than it was during his earlier two terms. Thus, rather than campaign by citing a strong Russian economy, Putin turned to Russian nationalism and military strength to garner support. The annexation of Crimea (part of Ukraine) in 2014 sharply bolstered his approval ratings, as Putin positioned the move as being protective of the freedom and self-determination of ethnic Russians (although fewer than half of the Crimean population voted to join the Russian Federation). It is also well-remembered that Putin was no champion of the Chechnyan separatists’ desire for self-determination; his brutal crack down on that ethnic group’s rebellion in 1999 as Prime Minister garnered him high marks with the Russian population. This casting of himself as the protector of “the motherland” and the one to restore Russians to the fold holds much appeal to a population where wealth is held and controlled by oligarchs. As the Russian economy is heavily impacted by the price of oil, economic performance is volatile; the nation’s GDP suffered enormously during the COVID pandemic. Putin’s promise of a strong Russian national and cultural identity plays a large role in his public speeches. In his February 24, 2022 speech on the Ukrainian invasion, Putin refers to the West’s attempts to “destroy our [Russia’s] traditional values” and frames his “special operations” as a program to “demilitarize and denazify” Ukraine. In Putin’s version of history, Ukraine must be liberated from a “junta” that is holding Russians hostage there. By positioning Russians as the historical victims at the hands of Western aggression (including the Nazis), Putin sets the stage for the Russian people to be ready to sacrifice in the name of national identity: “..it is our strength and our readiness to fight that are the bedrock of independence and sovereignty and provide the necessary foundation for building a reliable future for your home, your family, and your Motherland.” Putin’s approval rating has soared since the Ukrainian invasion, near 80 percent as of April 2022. Iron-clad control of media and information dissemination within Russia, as well as a vast web of social media bots and trolls, help to shape this view of Russians as protecting their territory, national identity, and culture. In a country where Economic Man has clearly failed, and where there is little else to shore up hope and stave off despair, Putin uses the playbook of Heroic Man, calling on personal sacrifice for the greater good of the Motherland. Then the “very elements of irrational warfare” can become perfectly rational. In all of this horror unfolding, I find a little comfort in Drucker’s assessment of the ultimate demise of Heroic Man as a worldview. The system requires the constant identification of enemies, of boogeymen who threaten the society, requiring self-sacrifice on an increasing scale. Drucker says that, because fascism cannot create a functioning society, it must justify itself through the persecution of enemies: “Perpetual unrelenting warfare against them becomes a holy task which not only permits but demands brutality, violence, and deception” (p. 197). Putin’s references to Nazis in Ukraine (a nod to the fact that some Ukrainians did aid the Germans during their occupation of Soviet Ukraine) provide this kind of justification for the Russian population. Putin similarly invoked NATO as a threat to Russian safety, national identity, and power. Yet, such a model of Heroic Man, of sacrifice to the holy cause, is unsustainable. A society based completely on noneconomic factors, mainly military sacrifice, cannot be sustainable: “This inevitable failure to base a society on the anarchic concept of Heroic Man vitiates irreparably the entire performance of totalitarian fascism. It renders impossible the successful solution of class war, as it frustrates its replacement by the new social noneconomic harmony of the nation in arms” (p. 195). If Drucker is to be understood, Heroic Man may resurface when conditions are ripe, but that worldview cannot be sustained. Ultimately, Russia (and other totalitarian regimes) must find another path. I don’t know. Some pundits are saying that Ukraine spells the end for Putin’s reign. Yet the popularity of far-right populist leaders such as Marie Le Pen in France and Viktor Orban in Hungary indicate that there is an appetite for “strong” leadership that calls for a Heroic Man worldview. In societies where there has been a breakdown or perceived loss of “genuine values” or a “valid creed”, how can a functioning society exist? How can such societies avoid a strain of nihilism or similar self-destructive philosophy? I have concerns about this in the United States as well. The pandemic did not bring us together under an umbrella of social cohesion fighting a common enemy (the virus). Instead, it resulted in politicization of science, where public health policies (masks, social distancing, and vaccinations) became fodder for arguments about freedom. The perceived loss of status and function that fueled the populist movements of the Tea Party and Donald Trump have only been exacerbated by the economic disruptions of the pandemic, which have exposed longstanding wealth inequality and cultural differences between urban and rural Americans. Many Americans no longer trust basic institutions of society (journalism, elections, the Supreme Court). A loss of a “valid creed” or “genuine values” has led people to sacrifice themselves for nonsense (Qanon, the January 6th insurrection based on a lie, etc.). The sources of despair today do not just lie in inflation. They are deep seated and long in the making. As the Western world unites around Ukraine against Russian aggression, perhaps we can find common ground in an identity that is not necessarily rooted in Economic identity, nor Heroic identity, but Drucker’s ideal of a new, noneconomic concept of “free and equal.” What would that look like? Like our Vision here at MLARI: A functioning society of institutions that ethically respects all of its constituencies and resists totalitarianism and autocracy in order to realize individual dignity. Citations: Aslund, Anders. “The Russian Economy in Health, Oil, and Economic Crisis.” Atlantic Council , May 27, 2020. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/commentary/long-take/the-russian-economy-in-health-oil-and-economic-crisis/ Friedman, Thomas. “Putin Had No Clue How Many of Us Would Be Watching.” The New York Times , April 3 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/03/opinion/ukraine-russia-wired.html Kendall-Taylor, Andrea and Frantz, Erica. “The Beginning of the End for Putin? Foreign Affairs , March 2, 2022. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russian-federation/2022-03-02/beginning-end-putin